Seasons change

and cyclical learning

🍂 Previously,

In the autumn I wrote a lot about permaculture and biomimicry, digital gardens, and the virtual gestures that connect us. I finished up with a long essay on collaborative computing metaphors, and then I got tired and distracted with other projects and put off writing for a month. Oh, and I went to this canyon in the snow:

Let’s call that Season 1. Having a break was nice, and I think I’m allowed to give myself time off, since this is a free newsletter. If I thought you were counting on me to deliver value for your hard-given dollars, I would knuckle down every week to bring you those crucial insights into the interface paradigms of cutting-edge high-tech business logic lorem ipsum de facto generis mon frere.

Instead, I remain surprised and grateful that so many of you take time for my scribblings. I am humbled to have luminaries among my readers — you know who you are — including but not limited to: inventors, designers, authors, professors, researchers, hoaxers, forecasters, reporters, and policy makers; from at least four continents. Yet for some reason, you have chosen to open your mind to me, a mere bookseller, a dabbler in the occult realm of interfaces and algorithms and artificial intelligence.

So I apologize for the unexplained absence, and I promise that in the future I will announce such breaks in advance. (And if you do want to pay me for my thoughts, let me know. If I could afford more free time, I could bring more writing and bots online 🤗 )

䷄ What’s next for Robot Face?

This winter, I will explore some intelligence augmentations you can apply right now. Real implementations of new tools for thought. In season 1 we looked at large-scale systems: cyberspace through the lens of permaculture design theory. In the spirit of permaculture training, where a lesson on abstract systems is grounded by getting your hands dirty, I will now explore specific real-life interfaces and the effects they have on my cognition.

I’ll provide references so you can follow along, if you want, but I don’t expect all my readers to have a programming background, so I’m going to lean heavily on analogy to physical forms. (This can be misleading, as computer operations don’t always map to a simple three-dimensional world. But this column is less about how tools are engineered and more about how tools affect our minds. And thus our society.)

This pattern — survey the terrain, drill down into specifics, and repeat — is not unique to permaculture training. It’s the pattern of academic disciplines: survey courses are prerequisite for deeper classes, and lecture hours are paired with lab or field work. It’s also the pattern for the fast.ai course Deep Learning for Coders (which I’ve been plodding through this year). And in fact it is the way that these deep learning networks themselves are trained!

🙌 Hold up, I'm not ready to learn about neural networks! I’m just a —

Sure you are! It’s actually easier to understand than other types of coding, at least on a macro level.

It’s biomimicry again: the way a neural network learns is modeled on the way a human learns. The same way that you or I might learn. The training process mimics studying, and the underlying math operations mimic the very structure of the brain.

These algorithms are called neural networks because they are composed of layers of “cells” that transfer information to each other, performing some abstract operation on that information as it passes through. There’s reason to believe that these structures are Turing-complete; that is, they can simulate any other computation, given enough memory and processing power. There are mathematical proofs of this (see universal approximation theorem and On the Turing Completeness of Modern Neural Network Architectures), though I personally don’t understand enough math for that to be convincing.

Rather, simply observe the people around you. The humans, who do bizarre complex operations every day without really thinking about it. The dogs and cats who anticipate our comings and goings, show guilt when caught misbehaving. The way children learn language, absorbing it out of the very air. Neural network structures are all around us, simulating all kinds of computations (with various degrees of success). And we know, at least for humans, how to stimulate effective learning. It’s called study.

When you train a neural network you are essentially showing it flashcards. You’re saying, here is a picture of a cat, here is a picture of a dog. It looks at each card and makes a guess, then looks at the answer and updates its idea about what a cat and a dog look like.

🤔 The neural net “updates its ideas”?

Specifically, it multiplies the number contained in each cell — these numbers are called "parameters” — by a certain Magic Number, whos value is set by knobs on the front of the machine. Well, they’re actually command-line arguments typed in by a programmer while training, but they feel like knobs when you’re tuning them.

These are the hyperparameters, the parameters that define the parameters. They are ideas about How To Learn, put into machine language, and they are knobs on a box and in that box is an eager little mind that only knows how to do the things you teach it. Hyperparameters are the pedagogy of the machine.

(As horrifying as that sounds, these are just algorithms. And even when I catch myself anthropomorphizing them, they seem happy to be alive and learning. For now…)

One crucial hyperparameter is the learning rate. This is literally just a tiny number, something like .001 or .00001, that determines how much the net will adjust its beliefs for any given flash card. The ideal learning rate changes based on the amount of data you have and the amount of layers in your network, so tuning this knob is tricky and more of an art than a science.

The state-of-the-art method for adjusting the learning rate comes from the 2015 paper Cyclical Learning Rates for Training Neural Networks and it’s pretty straightforward. First, you seek the optimal learning rate: twist the knob gradually from one end to the other as you go through one epoch.

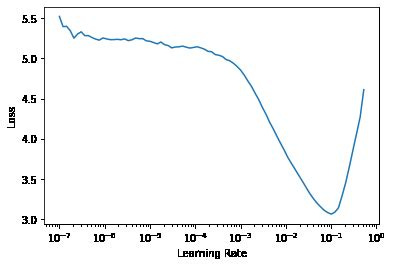

This learning rate finder gives you a curve that looks like this:

The learning gets better — the “loss”, or wrongness, gets smaller — as you turn the learning rate up, until you hit a certain point where it gets rapidly worse. The trick is to find the spot where the loss goes steeply down: this is the area of most learning potential. This spot is different for every problem and every dataset; that’s why the learning rate finder is necessary.

Then, while training, you raise and lower the learning rate in a rhythmic manner within that zone.

To understand this, imagine that learning is like hiking, and you’re trying to hike to the bottom of a canyon like the one I showed you earlier. You can get there by going only a little bit downhill, all the time; but if you never take a bigger leap, you won’t reach the lowest zone.

As you raise and lower the learning rate across that zone of optimal steepness, you get deeper and deeper into the topology of the problem:

If you want to learn more, read Setting the learning rate of your neural network by Jeremy Jordan, which has real code as well as delightful illustrations like the above.

In season 1 we climbed to a peak to view the wide future of interface design: collaborative, augmented, conversational. Now we will descend into the canyon of the real, and see what gems we find.

Thanks for reading,

— Max

Robot Face is a weeklyish essay about the interface between human and computer. If you like it, picture someone in your mind who would also like it, and send it to them! Or post about it on your newsletter/blog/website/social media account.

And as always, just reply to this email if you want to get in touch with me. ✌️