See and Point

and the Anti-Mac Interface

🕰️ Previously,

I wrote about how our online worlds are limited by the way they're built: the share/like/comment/follow architecture, built atop the chronological stream.

It's like a parade. You sit around, watch the traffic flow by. You can sit on the sidelines, applaud and heckle, or follow characters you like as they flow through the crowd. The loudest, most extravagant balloons set the tone. The rest of us get loaded and watch the show.

It's a social structure that assumes its users are passive consumers; or, at best, paying subscribers. You can watch the stream, you can make things and insert them in the stream, you can tip your favorite balloonist. Society as live entertainment.

This See and Point mode of interaction goes all the way back to the Macintosh, the common ancestor of modern GUIs. It supplanted the Remember and Type interface of the command line.

The Mac didn't actually pioneer all that much, computing-wise. It's not even the origin of the "desk" metaphor. But it was the first computer to default to desktop mode, instead of the command line. This made it friendly to new computer users.

You are in charge of the desk. Everything stays where you put it; you arrange your documents and icons around your virtual cubicle. This is called the WIMP model (yes, really): Windows, Icons, Menus, and Pointer. It influenced Windows and Linux, and evolved into the touch interfaces of first the iPod and then the iPhone. Touchscreens are the natural evolution of See and Point.

Graphical user interfaces have converged into the smartphone. This branch of the evolutionary tree has been perfected. An iPhone is like a shark: it doesn't have to change. It just gets a little better at being an iPhone every generation. But it's not the only way, nor the best.

🤔 What other interfaces could evolve?

The Mac was designed under constraints that we can now surpass. These constraints were analyzed in the 1996 paper The Anti-Mac Interface, from then-Sun Microsystems developers Don Gentner and Jakob Nielsen:

It needed to sell to "naive users," that is, users without any previous computer experience.

It was targeted at a narrow range of applications (mostly office work, though entertainment and multimedia applications have been added later in ways that sometimes break slightly with the standard interface).

It controlled relatively weak computational resources (originally a non-networked computer with 128KB RAM, a 400KB storage device, and a dot-matrix printer).

It was supported by highly impoverished communication channels between the user and the computer (initially a small black-and-white screen with poor audio output, no audio input, and no other sensors than the keyboard and a one-button mouse).

It was a standalone machine that at most was connected to a printer.

They go on to conjure a computing system that reverses every principle of Macintosh design.

The authors suggest that it might be a few years before these capabilities are implemented. A quarter-century later, the Anti-Mac is making its debut:

A ubiquitous computer, with language as its basic metaphor, constantly tracking your data and bringing information to you.

The technical capabilities required for this design turned out to be much harder than anyone projected. But finally, we're seeing progress. Computer vision, natural language understanding, and speech processing are near human capability, and "AI assistants" are preinstalled on all the major operating systems.

But consumer-grade systems have to change gradually, or they'll scare away their users. So these changes appear one by one, getting people used to the idea of a machine where "information comes to you".

And it doesn't always show. For instance, modern smartphone cameras actually take a bunch of photos every time you hit the "shutter" and choose the best-looking one to save. The phone doesn't tell you it's doing this, because that would insult your artistic pride. It helps quietly, unobtrusively. The algorithm is an extension of your hand.

This is intelligence augmentation in practice.

So the roadmap for the next major advance in computing is laid out in this 1996 paper, and all the tech giants can see it, and now it's just about who can grasp it first. The winner will have more people, more data, better AI, in a virtuous cycle. In all likelihood, this company in in the operating system space right now, though I wouldn't venture to say yet who will win. In any case, the operating systems of the future will look very similar, no matter their brand.

👾 What will the operating system of the future look like?

Obviously the business plans of each company are closely-kept secrets. But if you want a vision of the next interface, take a look at the design fictions created by university students and freelancers.

In particular, let's look at Artifacts, a bachelor's thesis by Nikolas Klein, Christoph Labacher and Florian Ludwig in 2017. (website, thesis PDF)

Artifacts is a human-centered framework for growing ideas. . . It is built for humans to continuously develop ideas over longer periods of time and emphasizes collaboration as a part of the system.

Crucially, "collaboration" here doesn't just mean with other humans. The Artifacts system is in an active communication loop with the human operator. It brings the information to you, so that you can do less folder-sorting and more idea-developing.

An "artifact" is the granular unit of this system. Instead of a "file," which might have a particular location on the hard drive and be copied or moved or deleted, an artifact is a single definitive unit of information that can be referenced from multiple locations. The system tracks your history, reads all your documents, scans all your photos for faces and objects, making everything searchable.

Artifacts can be linked, transcluded, tagged, versioned, filtered; the system is configurable to your needs. In fact, it attempts to model your behaviors, and adapt. The framework sends relevant artifacts to a panel called the Drawer, which you can open at any time for inspiration.

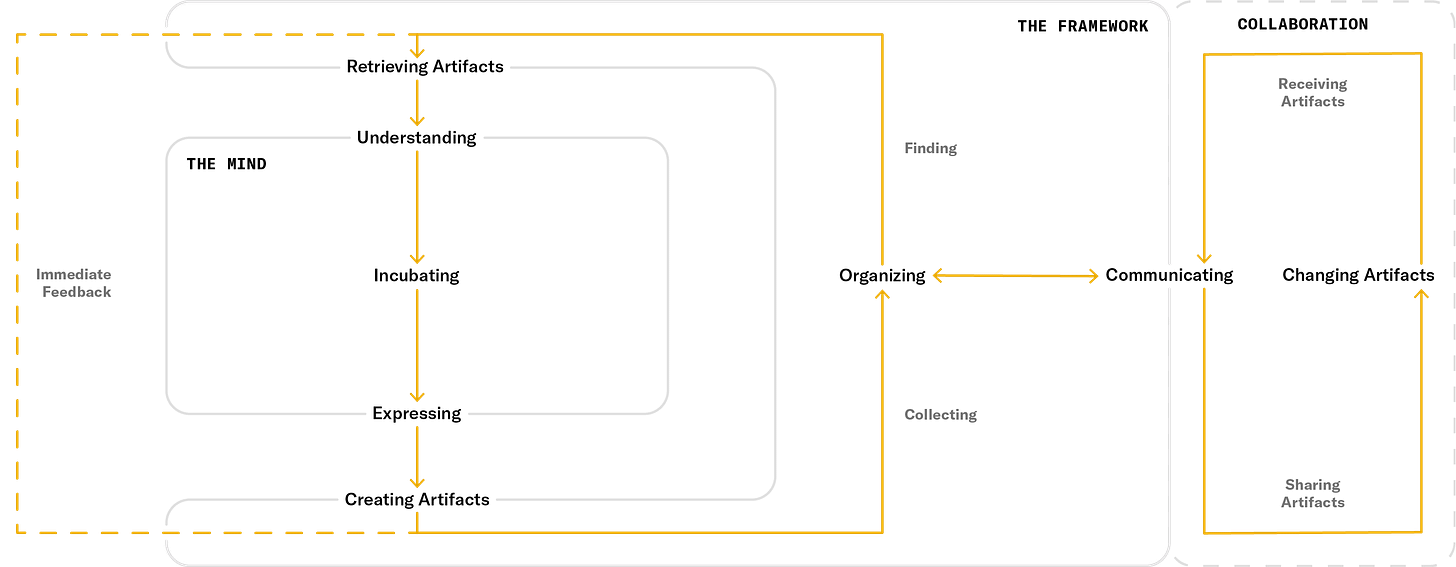

The Artifacts loop connects outside resources, like newsletters, or Wikipedia articles, or images someone sent you from their camera app (COLLABORATION); with internal resources, all organized and interlinked (THE FRAMEWORK); and presents them to you (THE MIND). This is called Retrieving Artifacts: your news feed, your search result, your Drawer contents.

You accept the Retrieved Artifacts through your Understanding skill, then process it through the very normal human faculty of Incubating. Finally you Express yourself into the machine, which absorbs all different types of input and creates Artifacts from them. Your work is done.

New Artifacts are Organized into THE FRAMEWORK and Communicated to the outside network. THE FRAMEWORK retrieves new artifacts for you to understand. Your work begins anew.

🙊 Sounds horrible. Why would anyone want that?

Maybe it will be horrible, this future of constant Understanding, Incubating, and Expressing. Surely there's a interface metaphor better than either Parade or Knowledge Work. But the idea that the computer will bring the information to you is not going away, for two reasons.

One is material: the technologies for the Anti-Mac are finally unleashed, and that means a lot of money is on the table.

The other reason is more mystical: people want to talk to their computers. Sure, plenty of people will tell you they don't want their machines to listen to them. But I don't think that's it. I think people don't want to be misunderstood.

This was the reason that GUIs caught on, after all. The naive user didn't want to be lost in the dark maze of the command line. They wanted a bright, clean, skeuomorphic desktop.

The graphic interface was already the computer adapting to the human mind. It found a Desktop metaphor available in the office worker’s mind and it morphed to fit. The design traded abstract power for precise control: if you know the secret commands, you can do sorcery. If not, you can micromanage this WIMP and do it manually.

But kids are already growing up with Alexa as nursemaid. In the future, they will expect their computers to talk to them, and the constraints have been lifted. You will no longer need to remember arcane shell commands to be a power user. You'll express your needs, and the computer will translate that into action, and update its model of you accordingly. It will anticipate your needs, offering sage advice or handy shortcuts.

Instead of pointing mutely at a window full of menus, you will express yourself fluently, with all the abstract power of language. Instead of a WIMP, you will be a partner in a Collaborative Human-Agent Dialogue -- a CHAD.

Thanks for reading,

— Max

This is Robot Face, a free newsletter about interfaces. If you liked it, make it “enter” someone else’s “face” by forwarding this email, or sharing it on social media parade.

If you have thoughts, I would love to hear them. Just reply to this email.